Innkeeper and farmer rebel from Kürzell. Farmer’s clever, brave and cunning ”, so or something like that describe the existing biographies of the Kurzeller Kreuzwirt Johann Georg Pfaff, who from April to September of the year 1797 in the so-called“ Second Coalition War ”with cunning and trickery against the then again and again invading and plundering French soldiers.

It is thanks to his courage and wealth of ideas that the community of Kurzell was spared looting and other acts of violence for a long time, while the neighboring towns were repeatedly and sometimes in the most brutal way robbed by the French, the houses were burned down and the residents were subjected to the most terrible reprisals had to suffer. It is understandable that Johann Georg Pfaff became a dazzling figure who gained a legendary reputation during his lifetime.

Later biographers or historians called Johann Georg Pfaff, who went down in the history of the Rieddorf Kurzell as a “folk hero in difficult times”, a “peasant rebel” and was even praised as the “Baden Andreas Hofer”. Even with Friedrich Hecker, one of the most famous revolutionaries from 1848/49, Johann Georg Pfaff was placed on one level. In Volume VI of the “Biography of Baden History” he is referred to as the “innkeeper and guerrilla leader in the Second Coalition War”. Already in 1835, during the lifetime of the “hero” the then Kurzeller parish administrator Johann Spinner published a 41-page biography under the title “Strange incidents and heroic deeds of Georg Pfaff, Kreuzwirt zu Kurzell”. It was not until 1894, almost 50 years later, that the Lahr calendar “Der Vetter vom Rhein” brought Pfaff’s deeds back to mind. In 1904 Pastor Heinrich Hansjakob also remembered the heroic deeds of the Kurzeller Kreuzwirt in his “Summer Trips”.

In 1913 the Freiburg “Caritas Verlag” published an extensive biography entitled “A People’s Hero in Hard Times”, which the author Karl Rögele wrote as a contribution to Baden’s local history at the time of

Wars of Liberation. In 1924, in his book “Heimatkunde des Amtsbezirks Lahr”, R. Seyfried recalled the life of the “Kreuzwirt Pfaff” from Kurzell. In addition to a few other essays, the essay by Heinrich Krems, published in “Die Ortenau” in 1941, should be mentioned

Great-great-grandfather commemorates the 100th anniversary of his death on September 19, 1940. “Der Altvater”, the former supplement to the Lahrer Zeitung, also dealt with the Kurzeller folk hero. While Emil Baader remembered this life story in 1940 on the 100th anniversary of his death, Emil Ell

on the 140th anniversary of his death in 1980 again accepted the “strange and heroic deeds of Johann Georg Pfaff, Kreuzwirt zu Kurzell”.

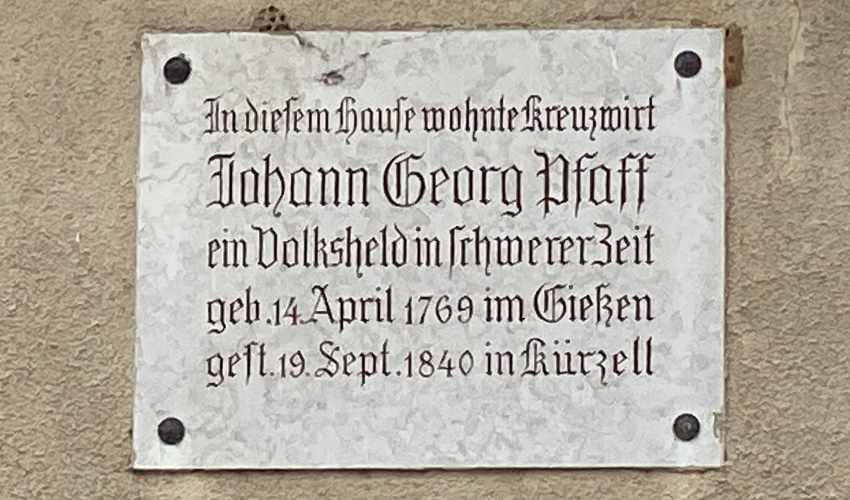

In his place of residence, Kurzell, only a memorial plaque attached to his former home, the Gasthaus “Kreuz”, as well as a portrait in the guest room itself as well as in the Kurzeller town hall reminds of this man

Recognize the heroic commitment of Johann Georg Pfaff for his place of residence and his fellow citizens. The following remarks are therefore intended to give a brief overview of his life and the time at that time.

In 1913 the Freiburg “Caritas Verlag” published an extensive biography entitled “A People’s Hero in Hard Times”, which the author Karl Rögele wrote as a contribution to Baden’s local history at the time of

Wars of Liberation. In 1924, in his book “Heimatkunde des Amtsbezirks Lahr”, R. Seyfried recalled the life of the “Kreuzwirt Pfaff” from Kurzell. In addition to a few other essays, the essay by Heinrich Krems, published in “Die Ortenau” in 1941, commemorates his great-great-grandfather on the occasion of his 100th anniversary of his death on September 19, 1940. has dealt with the shortened folk hero. While Emil Baader brought this life story to mind on the 100th anniversary of his death in 1940, Emil Ell again took on the “strange and heroic deeds of Johann Georg Pfaff, Kreuzwirt zu Kurzell” on the 140th anniversary of his death in 1980.

In his place of residence, Kurzell, today only a memorial plaque attached to his former home, the Gasthaus “Kreuz”, as well as a portrait in the guest room itself as well as in the Kurzeller town hall reminds of this man recognize Johann Georg Pfaff’s heroic commitment to his place of residence and his fellow citizens. The following remarks are therefore intended to give a brief overview of his life and the time at that time.

Johann Georg Pfaff was not a short-lived child, even if from 1789 until his death in 1840 he probably spent most of his life as the host of the “Kreuz” inn in the Rieddorf. The “Hintere Giesenhof” near Reichenbach in the Schuttertal, which was demolished in 1912, was the home of Jakob Pfaff, born on April 14, 1769 as the son of the farmer Jakob Pfaff and his wife Anna. Ketterer born later folk hero. The parents decided early on that the boy should one day take over the almost 400-acre yard.

At first he could not escape this request of his parents. That is why he stayed on his parents’ farm after finishing the “Latin school” he had attended in Gengenbach Monastery and ran the estate together with his father. Due to his lively temperament, he simply couldn’t stand the lonely courtyard, which is about three quarters of an hour’s walk from Reichenbach. That is why his father allowed him to do an apprenticeship at a bakery in Seelbach in order to later take over the “Vorderen Giesenhof”, which is also owned by the family. This farm, located about 20 minutes’ walk from Reichenbach, not only included 142 acres of land, but also a mill, which in turn was connected to a bakery. As was customary at that time, the young baker went on a journey after completing his apprenticeship. So he spent his journeyman time first in Freiburg, later in Colmar and then again in Freiburg. After the father suddenly died, he had to return home and should now, as planned, take over the “Vorderen Giesenhof”. But the young journeyman baker did not like the work on the farm, which is also quite lonely. So he left the property and moved to his stepbrother in Kurzell, who owned the “Zum Kreuz” inn there. There in the inn, which was on the former main street of the village, which at that time still led to Hugsweier, he liked it much better in view of the pulsating life. Therefore, in exchange with his stepbrother, to whom he left the “Vorderen Giesenhof”, he took over the manorial-looking Kurzell inn, which, as the biographies report, also had a bakery attached at that time. After he married Katharina Sandhaar from Biberach in the Kinzigtal on August 6, 1789 at the age of 20, the young couple moved into the stately property in Kurzell the next day. As Karl Rögele writes in his book published in 1913, Johann Georg Pfaff soon became an extremely popular man thanks to his excellent entertainment skills and his cheerful and honest disposition, which is probably one of the reasons why he quickly gained reputation and wealth.

The effects of the French Revolution on the population on the right bank of the Rhine. At about the same time, the French Revolution broke out. The revolutionary events also met with a strong response on the Upper Rhine. Strasbourg had its revolution on a small scale: like the Bastille in Paris, the prisons were opened there, the military mutinied, and on July 21, 1789 the town hall was stormed. In the process, the medieval city constitution, once admired far beyond the German border, was lost. A not inconsiderable part of the population on the right of the Rhine also sympathized with the thought processes of the French Revolution, so that the uproar also extended to the right-hand bank of the Rhine. Everything was in great turmoil. Since there was enough fuel for a revolutionary movement, acts of violence occurred above all in the areas of the monasteries Schwarzach, Frauenalb, Gengenbach, Schuttern and Ettenheim Munster. The enthusiasm soon died down, however, when the news of the terrible horrors of the Red Jacobins in Paris and throughout France spread across the Rhine. But especially after the storming of the Strasbourg town hall and the opening of the prisons, when French prisoners threatened to penetrate the Rhine and plunder. The inner danger in the margraviate of Baden was averted when, from 1792 onwards, French revolutionary armies broke out on all sides to bring “war to the palaces and peace to the huts”. Because in November 1792 the French National Convention declared that the French armies should provide aid to all foreign peoples who ask for assistance in the fight against the local rulers. This meant nothing other than that the French National Convention wanted to support the republican form of government in the other European countries as well. That is why the young French republic took up Louis XIV’s policy of conquest again. As a result, Ortenau not only once again became the scene of warlike entanglements, but also heralded one of the darkest decades in the history of war on the Upper Rhine. Because after Baden had first military allied with Austria and later with Prussia in 1791, revolutionary France in 1792 declared war on Austria, which was linked with Prussia, and thus also with Baden. Up until the peace of Tilsit, which was concluded in 1807, the margraviate of Baden was the focus of events every day as a march, march through and stage area.

If, with a few exceptions, the Ortenau was initially “haunted” by marching through troops and billeting, then after 1796, when the French had crossed the Rhine for the first time under the command of General Jean Victor Moreau near Kehl, they repeatedly plundered and plundered French revolutionary armies pillaging through the Ortenau. The French crossed the Rhine five times in our area. Each time they left a trail of horror. They had promised “Peace to the huts” and they raged with the utmost cruelty. Therefore, the inhabitants of the villages along the Rhine fled with their belongings to the forests adjacent to the villages, to the Rhine islands or to the Black Forest. Where it was not possible to escape, all supplies, all money or other assets were hidden. With fear of death these people had to face the approaching horror and defenselessly endure all abuse. Because in order to get to the presumed hidden property, the French intruders tied, beat and tortured the owners to such an extent that many died as a result of the abuse they suffered. However, one should not think of the French soldiers as a militarily uniformed army in today’s sense.

In his biography, Karl Rögele describes their appearance in great detail: One wore peasant clothing, the other in turn a clerical garb. Still others wore monk’s robes or even women’s clothes. One had a cap on his head, the other a hat. The clothing of the French in retreat was particularly striking. One saw soldiers there in choir coats, vestments, sheets, and even the dresses of women religious they wore. You carried what you had just stolen or stolen together. Most of the soldiers weren’t even wearing shoes. ”In this guise, the French raided villages and towns, robbed and plundered them with a frenzy that knew no boundaries. Whatever was of any value they took away or destroyed it. Especially on their retreat, the destructiveness knew no bounds. Windows and all furniture were smashed, beds cut up and the feathers scattered in the wind. They hollowed out the bread many times and refilled it with their excrement. Flour and grain were made unusable by mixing them with oil and sand. Wine that they could not take away was poured out in the cellars. Churches were robbed, pictures smashed, altars contaminated, chalices and vestments stolen and misused. In many cases, houses were also set on fire, from which the sick and decrepit people found it difficult to escape. The food was stolen or spoiled, the crops in the fields destroyed. They left nothing but hardship, misery, crime, hunger and disease. Neither the surviving inhabitants nor the Austrians who followed the French found hardly any food. It is very difficult to get a rough idea of the damage that Ortenau suffered in the four coalition wars. The majority of the files were lost as a result of the war. That is why not everything that the inhabitants suffered from the Soldateska can be proven in terms of sources. The material damage suffered cannot be described either. However, many individual descriptions result in a very clear mosaic picture. How great the extent of the devastation must have been after the First Coalition War, however, emerges from a report by the French General Laval of January 27, 1794 to the convention in Paris. Nowhere are the atrocities and inhumanities committed more clearly described:

“We have taken so much from the subjects of this area that they have nothing left but their eyes with which they may weep over their truly indescribable misery. “The Catholic Dean Michael Hennig also describes the situation at that time very clearly in his“ History of the Lahr Land Chapter ”published in 1893. There it says among other things: The arrival of the French was a terrible one and spread such fear that many fled and hid their belongings. Almost all pastors also fled, some hiding in the woods, some looking for safety in more distant areas. The service stopped in many areas, the pastoral care was hampered for a few days. Wherever the French army went, it left lamentable traces. Often the tabernacles were broken into, the holy of holies desecrated, sacred vessels and vestments stolen. They plundered the homes of the rich and the poor. The residents insulted, insulted, beat and threatened many with death. It is understandable that the years between 1792 and 1805 offered the population in our homeland a level of suffering that could hardly be surpassed. A brief description of the warlike events at that time After the French army crossed the Rhine at Kehl for the first of five times on the night of June 23rd to 24th, 1796 under the command of General Moreau, the Kurzeller Kreuzwirt Pfaff fled with him Family to his brother at his parents’ Giesenhof near Reichenbach. An escape that, in retrospect, was of no use at all. Because the French also found the lonely Giesenhof and stole everything that fell into their hands in the way of money and food. After the French left, Pfaff and his family returned to Kürzell.

On April 20, 1797, the French Rhine and Moselle Army crossed the Rhine for the second time at Diersheim below Kehl, again under the command of General Moreau. Just two days later, on April 22nd, the French troops were in Niederschopfheim, Meißenheim and Kurzell, and on April 23rd in Kappet, Ettenheim and Lahr. Then came the news of the Preliminiar Peace, concluded in Leoben on April 18, which ended the war between Austria and France for the time being. In accordance with the provisions of this armistice, both opponents maintained the areas that were in their outposts at the moment of the arrival of the message of peace. The French troops now in the country plundered and robbed the villages again in wild and unrestrained vandalism. In addition, they levied war taxes on the impoverished communities, demanded high taxes on food and feed from the population, and forced them to do labor. Those who resisted were mistreated. Officers and men lived in luxury at the expense of the impoverished communities. As in every other village in the area that they held, the French came from time to time to Kurzell and here too quickly confiscated everything they needed or what they liked. Although the looting and harassment must have hit Johann Georg Pfaff particularly badly, he stayed with his family in the “Kreuz”. Because not only that the French robbed him of the food supplies, they also booze in his restaurant at his expense.

Not until the end of January 1798, more than nine months after the provisional peace of Leoben, so long after the one on 17/18. On October 1797 the final peace of Campo Formios, which ended the First Coalition War, was concluded, and the French, who had been under the command of General Pierre Francois Charles Augera since September 1797, withdrew from the Ortenau again. Only one year later, on March 1, 1799, the French under General Jean Baptiste Jourdan crossed the Rhine for the third time near Kehl and Hüningen. However, after the Austrian Archduke Karl was able to decisively defeat them on March 25, 1799 near Stockach, they escaped through a hopeless escape through the Kinzig and Renchtal valley into the Rhine valley. At the beginning of April the army crossed the Rhine. However, since Archduke Karl had to come to the aid of the Russians connected with the Austrian Emperor in Switzerland, he could not take advantage of the victory he had won and force the entire French army across the Rhine. So Kehl and the wider area remained occupied by the French. From there the remaining French soldiers were able to do their mischief almost undisturbed throughout the whole of the year. Because there were only insufficient Austrian armed forces facing them, so that there were small battles almost daily in all parts of Ortenau. Here, the Austrians from Dinglingen waged a guerrilla war with the French. As a result, Kurzell was repeatedly between French and Austrian outposts. It was during this time that Johann Georg Pfaff’s heroic advocacy to save belongings and protect the lives of his fellow men.

Johann Georg Pfaff in the guerrilla war against the French As the organizer of a mounted scout troop, the Kurzeller Kreuzwirt, Johann Georg Pfaff, rendered valuable services to the Austrian cavalry division advanced to Dinglingen and helped to thwart the looting of the French in Kurzell, Schuttern and Dinglingen. As the Kurzeller parish administrator Joseph Spinner writes in his biography published in 1835, i.e. while Pfaff was still alive, it was also clear to the Kreuzwirt that he could only keep the French out of Kurzell and the neighboring villages with cunning. He was able to achieve his first success with a courageous plan. When the French looted again in Kurzell, he and three young Kurzeller farm boys, all armed with firecrackers, several pistols and the associated ammunition, sneaked unnoticed into the so-called “Eichwald”, which was then between Allmannsweier and Kurzell, when darkness fell. During the night they shot down the “ammunition” they were carrying at various points, so that the French feared that the Austrians were approaching with artillery and strong gunfire, and they fled.

This successful “skirmish” had a lot to thank not only for Kurzell, but also for Schuttern Monastery. There the French had looted everything again and had already loaded the captured goods onto several wagons for removal when they heard the alleged bombardment coming from Allmannsweier. They abandoned all the looted goods and fled in panic in the direction of the Rhine. In the period that followed, the Kreuzwirt made himself available to the Austrian troops as a local guide. During various reconnaissance rides he showed particular courage in the peasant costume of that time and always rode far enough alone that he could closely observe and determine the positions and strength of the French outposts. Thanks to Pfaff’s local knowledge and under his leadership, the Austrian Uhlans were able to ambush an enemy rider on call and take 31 prisoners without firing a shot. The successful skirmishes made Pfaff a local celebrity outside of Kurzeme. He therefore feared that his deeds would also become known to the French and that they would take revenge not only on him and his family, but on the entire village. Therefore, at his request, a vigilante guard with Kreuzwirt Pfaff as captain was founded in the municipality of Kurzell. The task of this armed vigilante group was to observe the French and, if necessary, to bring the Austrian Uhlans stationed in Dinglingen to help. Placidius Bacheberle, the abbot of the Schuttern monastery, which suffered particularly badly from the French, had him tailor-made a Uhlan uniform in recognition and thanks for his services. It is said to have consisted of a yellow cap with cords and a white plume, a red skirt, green trousers with red stripes and a white coat. Pfaff is also said to have bought a martial “mustache” that he always wore “on duty”, while he rode his fiery “Normänner”. Equipped like this, he must have looked respectful in any case, because from that point on, his Austrian friends only respectfully called him “Kadett Bauer”. Armed in this way, Pfaff took part in all Austrian ventures in the guerrilla war against the French occupiers.

Within only six months, the Austrians, with Pfaff’s assistance, were able to capture around 800 French soldiers. In the biographies mentioned at the beginning, every single skirmish in which Johann Georg Pfaff participated either as a captain of the Kurzeller vigilante group or as a patrol leader of the Austrian cavalry unit is described in great detail again and again. Certainly also somewhat heroic, he is described as a man who, with his presence of mind and bold determination, did not shy away from any danger, however great. The deeds that he performed as a volunteer in the service of the Austrian army are consistently described as very exceptional and rare military achievements for the time. For example, Karl Rögele rated these deeds in his biography published in 1913 as brilliant evidence of the courage, skill and courage of Johann Georg Pfaff. Regardless of which side you look at these acts, it is certain that Johann Georg Pfaff, thanks to his local knowledge, his cunning, his callousness and also his boldness, found his place of residence in Kurzell in the chaos of war at that time almost half a year before occupation, looting and many other things Preserved harassment from the French occupiers. During this period, Kurzell was spared from tribulations and acts of violence, while the surrounding neighboring towns were repeatedly robbed and plundered by the French, and many of the residents’ belongings were destroyed in the process. Pfaff’s deeds were not only thanked and recognized by his fellow citizens. His “war acts” were also followed with interest and attention in “higher places”. General Count Maximilian von Merveldt, who was in Austrian service and played a major role in the victorious battle of Stockach, told Archduke Karl about the services Johann Georg Pfaff had earned for the Austrians. At the suggestion of Archduke Karl, the Austrian Emperor Franz at 11.15 awarded the Kurzeller Volkshelden for his heroic deeds and achievements with the “Golden Medal of Merit.

Treason and capture of the Kürzeller folk hero

But even after the French had to back down from the vastly superior forces of Archduke Karl after the Battle of Stockach, the war continued. About a year later, the French Army on the Rhine, again under the command of General Moreau, marched on the border. Moreau’s main plan was to cross the Rhine with the right wing of his army from Switzerland. However, in order to conceal this intention and to distract the enemy, the left wing of the army crossed the Rhine again at Kehl on April 25, 1800 and pushed the Austrian corps back in several battles. On April 27, the French surprisingly withdrew again to join the main army via Breisach and support their operations. Soon the Austrians had to give up their positions in the Rhine Valley in order to concentrate all their forces against Moreau, who on December 3 was ultimately victorious against the Austrians in the decisive battle near Hohenlinden. To occupy the Rhine crossing in Kehl, larger detachments of the French army stayed behind and were quartered in the surrounding towns throughout the summer. Troop marches and digging were again part of everyday life at that time. In the headquarters, which the French had set up in cork, General Klein once again prescribed prohibitive requisitions, which the French again drove with all the hardship.

Above all, those villages that had so far more or less successfully fought against the ruthless approach felt the whole anger of the French occupying power. The Kurzeller Kreuzwirt had to fear for its safety more than ever. Nevertheless, out of consideration for his family, he turned down the offer to take up an officer position in the Austrian army command. However, for security reasons, he initially stayed with friends. It was only after he had entertained the French several times during the day without their seeming to notice him that he slept at home again. As a precaution, he set up a hiding place under the adjoining room of the guest room, which should offer him protection and security in an emergency. However, when a former Austrian Ulan corporal who defected to the French and who was present at one or the other earlier coup d’état by Pfaff had betrayed him to the French General Klein in Kork, one night a mounted unit surrounded the inn and asked for admission. Pfaff, who immediately recognized the danger, hid himself in the prepared hiding place. But when every hideout of the house was searched unsuccessfully, the French threatened to set the property on fire from all four sides. Therefore, Pfaff revealed himself to the French who captured him and immediately brought him to Kork. Since the margraviate of Baden had declared itself neutral during the war, Pfaff was suspected of espionage, since he served the Austrians as a scout. That is why he was subjected to a three-hour interrogation by General Klein the next day. Pfaff defended himself extremely skillfully, so that he was released the following day.

Closing remarks

After the times had become more peaceful again with the peace treaty of Lundville 20 of February 9, 1801, Johann Georg Pfaff devoted himself entirely to his family and his business, which, however, had declined sharply as a result of the chaos of war in those years. However, Pfaff did not have peaceful years. In addition to the death of his first wife, there were also some serious economic slumps. It was only through tremendous diligence that he was able to bequeath the “cross” to his son. On September 19, 1840, at the age of 71, Johann Georg Pfaff, who went down in history as a “folk hero”, died. Pfaff’s tombstone is still honored today in the garden of property no. 4 in the Kurzeller Jägergasse. Even if the “ravages of time” gnaw on him incessantly, the inscription is: Rip Johann Georg Pfaff born April 14, 1769 died Sept. 19, 1840 still easy to read. This simple tombstone and the formerly stately looking inn “Kreuz” have survived as the only silent witnesses of the past to this day. Used literature In addition to the literature mentioned at the beginning of the article, the following sources were also used:

- Meyers Hand-Lexikon des Allgemeinen Wissens, Leipzig 1883

- Paynes Conversations Lexikon, Leipzig 1896

- Dr. Manfred Krebs, „Politische und kirchliche Geschichte der Ortenau“, in „Die Ortenau“ Nr. 50/1960, S. 133-245

- Karl Stiefel, „Baden“, Karlsruhe 1977

- Kurt Klein, „Landum Rhein und Schwarzwald“, Kehl 1978

- Brockhaus Enzyklopädie in 24 Bänden, Mannheim 1990

- J. Stolzer und Ch. Steeb, „Österreichische Orden“, Graz/Austria 1996

Remarks The “morning” is an old German square measure that originally was the arable land that a farmer with a team could plow in the morning (morning). The “morning” differed considerably from region to region. One acre in Baden was 3,600 square meters.

Jean Victor Moreau (August 11, 1761, t September 2, 1813) was Commander-in-Chief of the Rhine and Moselle Army from 1796. On July 9, 1796 he defeated Archduke Karl near Ettlingen and then skilfully withdrew across the Black Forest. In 1798 he was commander in chief of the French army in Italy. In 1800 he was again appointed Commander in Chief of the Rhine Army, where he defeated the Austrians at Engen, Möskirch, Biberach and Memmingen. He was able to throw the Austrian army out of its permanent positions near Ulm and, after Siegen, advanced to Regensburg near Höchstädt, Nördlingen and Neuburg. On December 3, 1800, he won the decisive victory at Hohenlinden and concluded the Steyr armistice on December 25. On February 4, 1804, Napoleon Bonaparte had him arrested and exiled to America. He returned in 1814 and entered the service of Tsar Alexander I in Prague. After losing both feet to a cannonball in the Battle of Dresden on August 27, 1813, Moreau died just a few days later on September 2 in Laun (Bohemia ).

Leoben = district capital in Styria (Austria).

In international law, a preliminary peace is a preliminary peace with the cessation of hostilities with preliminary agreements reached and stipulated in preliminary negotiations that already contain the essential conditions of the (later) final peace treaty.

Campo Formio = village in the Italian province of Udine. In the Peace of Campo Formio Austria ceded the Austrian Netherlands, Milan and Mantua and confessed in secret articles the cession of the left bank of the Rhine to France. Austria received Veneto to the left of the Adige with Istria and Dalmatia.

Pierre Francois Charles Augerau, Duke of Castiglione, Marshal of France (“11. 11. 1757, t 11. 6. 1816) was promoted to brigade general in the Pyrenees army in 1794 and divisional general in the Italian army under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1796. In 1804 he was appointed marshal. In 1813 he became governor of Berlin. In 1813 he took part in the Battle of the Nations in Leipzig with a reserve corps. After Napoleon I abdicated, he joined Louis XVIII. over, who appointed him “pair” (pair = the highest nobility, who was originally equal to the monarch).

Jean Baptiste Jourdan (born April 29, 1762, dated November 23, 1833) became divisional general and commander in chief of the Northern Army in July 1793. After he had been given the command of the Meuse and Sambrearmee in 1794, the Danube Army was subordinate to him in 1799. Both at Ostrach (March 21, 1799) and at Stockach (March 25, 1799) he was subject to the Austrian Archduke Karl. In 1800 he was entrusted with the administration of Piedmont. In 1803 he entered the Senate and in 1804 was appointed Marshal and Councilor of State. In 1815 Louis XVIII appointed him. to the count and in 1819 also to the pair. In 1830 he became governor of the house of invalids.

Archduke Karl (born September 5, 1771, dated April 30, 1847), son of the Austrian Emperor Leopold II, took command of the Austrian Army on the Rhine in 1796 as the last Reich Field Marshal. Although he was militarily very successful, he retired from military service in 1799 because of deep conflicts with his imperial brother Franz II. In 1801 he became Austrian Minister of War as President of the Court War Council and began to reorganize the army from the central administration to the regiments. In the war of 1809, waged against his will, he won the much admired first victory against Napoleon as an independently acting generalissimo after initial defeats at Aspern. After losing the battle of Wagram, however, he initiated peace negotiations in the face of the collapse of Austria. For this reason he was removed from command and had to end his military career. As a military writer, he earned a reputation comparable to Clausewitz.

Recognizing means in the event of war, a terrain and investigating the conditions of the enemy.

Uhlans were a light or medium cavalry division with lances, carbines and sabers in the Austrian troops.

A “standby” was a troop detachment set up behind them to receive or support the field guards.

Placidius Bacheberle (“1745, t 1824), who on June 27, 1786 had taken over the abbot from his voluntarily resigned predecessor Carolus Vogel, was the last abbot of the Schuttern monastery.

The “poor norm” is likely to have been a horse of the “Anglo-Norman” breed. This breed of horse was bred in Normandy, where the influence of the landscape and climate resulted in a strong, resilient horse. The breed is descended from the Norman war horses of the Middle Ages, which were ennobled in the 18th and 19th centuries by crossbreeding with Arabs, English thoroughbreds and Norfolk trotters.

Count Maximilian von Merveldt (* 1764, d.1815), who came from a Westphalian noble family, was equally important as a military leader and as a diplomat. He took part in several campaigns and was in southern Germany in 1796 and from 1799 to 1801. As an Austrian army diplomat, he took part in the peace negotiations with Napoleon in Leoben, Campe Formio and Rastatt. From 1806 to 1809 he was the Austrian envoy in Petersburg. In the Wars of Freedom (1813-1815) he was in command of the Second Army Corps, but was captured on the very first day at the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig and the next day Napoleon I sent him to Emperor Franz II with peace proposals. In 1814 he became the Austrian ambassador in London, where he also died.

Franz II (born February 12, 1768, t March 2, 1835) was the last emperor of the so-called Holy Roman Empire. Shortly after his accession to the throne in 1792, revolutionary France declared war on Austria. In the peace agreements that followed the coalition wars, he suffered high losses of territory. In 1806 he laid down the Roman imperial crown and declared the Roman imperial dignity to have lapsed so as not to give Napoleon I the opportunity to seize this dignity. After the military defeats of 1809 he tried to get closer to Napoleon and therefore agreed to marry his eldest daughter Marie Luise to Napoleon I in 1810. In 1813, however, he joined the great alliance against Napoleon I.

The medal known as the “Golden Merit Medal” shows on one side the motto “LEGE ET FIDE” (as a result of a law and because of proven loyalty) and on the other the image of Emperor Franz II with the inscription: “Imp. Caes. Francis II. P.F. Avg. ”As the Roman-German emperor, Franz II distinguished between the medals of grace that were for the empire and those for the Habsburg hereditary land.

Hohenlinden = village in Upper Bavaria in today’s Ebersberg district (Alpine foothills between Munich and Rosenheim).

I could not find any reference to General Klein in the literature available to me. The General State Archives in Karlsruhe also have no documents on this French general (letter from January 15, 1999 – 11 AZ. A1-7512-Frenk, Martin).

Requisitions = type of food during war, in which the needs of the troops are collected from the inhabitants by the authorities of the occupied country and transferred to the military authorities.

On February 9, 1801, the Treaty of Luneville (city in France, located in Lorraine at the confluence of the Vezouse in the Meurthe) ended the Second War of Coalition between France and Austria and confirmed the Peace of Campe Formio. This peace treaty gave France, among other things, the left bank of the Rhine, while the German princes were compensated for the loss of territory on the left bank of the Rhine in the so-called Reichsdeputationshauptschluss.

The first marriage to Katharina Sandhags from Biberach had five children and the second marriage to Sabina Kurz from Abbreviation) had four more children.

Source: From the book “Riedprofile von Martin Frenk